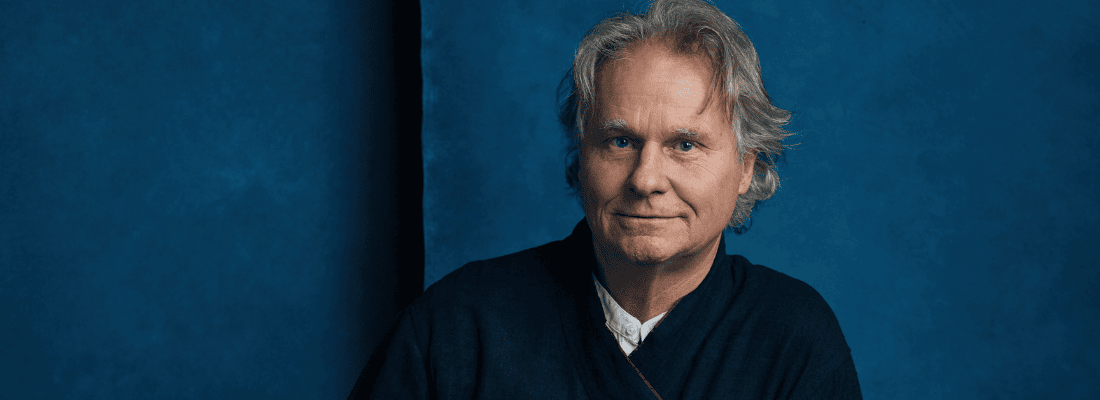

Keynote Speeches

Every culture is a unique answer to a fundamental question: What does it mean to be human and alive? Wade Davis leads us on a thrilling journey to celebrate the wisdom of the world’s indigenous cultures. In Polynesia we set sail with navigators whose ancestors settled the Pacific ten centuries before Christ. In the Amazon we meet the descendants of a true Lost Civilization, the Peoples of the Anaconda. In the Andes we discover that the Earth really is alive, while in the far reaches of Australia we experience Dreamtime, the all-embracing philosophy of the first humans to walk out of Africa.

We then travel to Nepal, where we encounter a wisdom hero, a Bodhisattva, who emerges from forty-five years of Buddhist retreat and solitude. And finally we settle in Borneo, where the last rainforest nomads struggle to survive.

Understanding the lessons of this journey will be our mission for the next century. Of the world’s 7000 languages, fully half may disappear within our lifetimes. At risk is a vast archive of knowledge and expertise, a catalogue of the imagination that is the human legacy. Rediscovering a new appreciation for the diversity of the human spirit, as expressed by culture, is among the central challenges of our time.

If the quest for Mount Everest began as a grand imperial gesture, as redemption for an empire of explorers that had lost the race to the Poles, it ended as a mission of regeneration for a country and a people bled white by war. Of the twenty-six British climbers who, on three expeditions (1921-24), walked 400 miles off the map to find and assault the highest mountain on Earth, twenty had seen the worst of the fighting. Six had been severely wounded, two others nearly killed by disease at the Front, one hospitalized twice with shell shock. Four as army surgeons dealt for the duration with the agonies of the dying. Two lost brothers, killed in action. All had endured the slaughter, the coughing of the guns, the bones and barbed wire, the white faces of the dead.

In a monumental work of history and adventure, ten years in the writing, Wade Davis asks not whether George Mallory was the first to reach the summit of Everest, but rather why he kept on climbing on that fateful day. His answer lies in a single phrase uttered by one of the survivors as they retreated from the mountain: ‘The price of life is death.’ Mallory walked on because for him, as for all of his generation, death was but ‘a frail barrier that men crossed, smiling and gallant, every day.’

As climbers they accepted a degree of risk unimaginable before the war. They were not cavalier, but death was no stranger. They had seen so much of it that it had no hold on them. What mattered was how one lived, the moments of being alive. For all of them Everest had become an exalted radiance, a sentinel in the sky, a symbol of hope in a world gone mad.

In a rugged knot of mountains in northern British Columbia lies a spectacular valley known to the First Nations as the Sacred Headwaters. There, three of Canada’s most important salmon rivers—the Stikine, Skeena and Nass—are born in remarkably close proximity.

Now against the wishes of all First Nations, the British Columbia government has opened the Sacred Headwaters to industrial development. Fortune Minerals proposes a coal operation that would level mountains. Imperial Metals is moving ahead with an open pit copper and gold mine on Todagin Mountain, home to the largest population of Stone sheep in the world; tailings from the Red Chris mine will bury Black Lake and leach into the headwaters of the Iskut River, the main tributary of the Stikine.

For years Royal Dutch Shell sought to extract coal bed methane gas across a tenure of close to a million acres, which would have implied a network of roads and pipelines and thousands of wells placed across the entire valley of the Sacred Headwaters.

For ten years Tahltan men, women and children, along with local non-native trappers, guides, and writers have stood up for the land, and in a remarkable grassroots victory in 2012, Shell Canada withdrew from the valley.

The struggle continues, and will continue until the entire Sacred Headwaters is protected. The resounding message of the people is that no amount of gold, copper or coal can compensate for the sacrifice of a place that could be the Sacred Headwaters of all North Americans and indeed all peoples of the world.

Plugged by no fewer than twenty-five dams, the Colorado River is the world’s most regulated river drainage. It provides most of the water supply of Las Vegas, Tucson, and San Diego, and much of the power and water of Los Angeles and Phoenix. If the river stopped flowing, we would likely have to abandon many of the largest cities in the West. The Colorado is indeed a river of life, which makes it all the more tragic that by the time it approaches the sea, it has been reduced to a toxic trickle, its delta dry and deserted.

In a blend of history, science and personal observation based on his experience as a white water guide and leading character in the 3D IMAX production Grand Canyon Adventure, Wade Davis tells the story of the American Nile, its geology and ethnography, the early explorations of John Wesley Powell, the critical role of the Mormon Church, the stunning engineering achievement of Hoover Dam and all the complex decisions that ultimately transformed the river, leaving it but a shadow in the sand as it reaches the sea.

The plight of the Colorado is a story of folly and loss, but also of immense hope, for we have it readily within our power to restore the river and its delta to life. Public perceptions aside, the water crisis in the Southwest is not due to people wanting golf courses in Phoenix, fountains in Vegas, swimming pools in San Diego. All such domestic uses amount to a minor percentage of the water diverted from the river, perhaps 630,000 acre-feet a year.

The water crisis in truth is due to one single factor—cows eating alfalfa in a landscape where neither belongs. The 250 million acres of land allocated by the Bureau of Land Management for cattle grazing yield less than ten percent of the national beef production. This supports a way of life rich in nostalgia, but hopelessly inefficient in terms of productivity and water consumption. The delta of the river, verdant in the lifetime of my father, could be restored with the amount of water that now goes to support a third of one percent of the nation’s beef production.

Similar Speakers 123